Scott A. Williams, New York University

Around two million years ago an ancient human relative, Australopithecus sediba, lived in what is today South Africa, nearby a cave called Malapa that’s a part of the Cradle of Humankind. Until recently, it was not clear how much the species spent climbing in trees and walking on two legs on the ground.

The discovery of a lumbar vertebra from the lower back of a single female Australopithecus sediba – with other parts of the same specimen’s vertebrae – has changed this. Scientists from New York University in the US, South Africa’s University of the Witwatersrand and 15 other institutions have published a journal article that shows Australopithecus sediba walked like a human but climbed like an ape. The Conversation Africa’s Natasha Joseph asked lead author Scott A. Williams about the research and its implications.

What was known about Australopithecus sediba before this research?

Quite a lot. This species was first discovered in 2008 (and announced in 2010); the recovery of new fossil material from Malapa has continued since then. That’s partly because on-site excavations have taken place since 2008, but also because large blocks that were removed from the site have been scanned with medical computed tomography (CT) to see if there are fossils inside. If so, the blocks are prepared down to reveal the fossils.

The new lumbar vertebra fossils came from one such block, removed from a makeshift road made by miners many years ago. They had blasted the site and used some of the large blocks to build the mining road – and they were blasting hominin fossils too.

Parts of two partial skeletons (juvenile male “Karabo” and adult female “Issa”) have been recovered in the remnants of the Malapa cave and outside it. So, we knew that there were at least two individuals at Malapa, that they dated to just under 2 million years old, and they were a distinct species – one that retained many primitive features of Australopithecus yet also had features of the skull, teeth, and skeleton that were more like members of our genus, Homo. It has been a very controversial species for that reason.

What prompted you to examine this particular set of fossils?

I wrote my dissertation on the evolution of the vertebral column in hominoids, a group that contains us and our closest relatives, the apes (chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, and gibbons). The announcement of A. sediba was published during that time and I wrote to Professor Lee Berger who discovered the first fossil remains with his then nine-year-old son asking about the vertebrae I could see in the figures in their publication. He kindly invited me to work on them and I have been doing so ever since.

We have already described the vertebrae that had been recovered up to about 2013 and, in 2018, published full, detailed descriptions and comparative analyses of the skeletons.

Initially, what we knew about Issa’s spine came from lower thoracic vertebrae, lower lumbar vertebrae, and a partial pelvis. Much of the lumbar column was missing.

But all the while, new fossils were being discovered – and in 2016, the new lumbar vertebrae were prepared. This allowed us to study Issa’s nearly complete lower back.

What did the new lumbar vertebrae reveal?

We were able to say a lot more about Issa’s lower back and adaptations to bipedalism (walking on two legs) than we could before. In 2013, we only had the two lowest lumbar vertebrae. From these, we found the bony wedging to indicate that Issa potentially had a highly lordotic – curved forward – lower back.

The new fossils allow us to include more lumbar vertebrae, which really balanced out our estimation of curvature to something quite similar to the degree of lordosis we modern humans have; in fact, Issa’s bony wedging was most similar to the modern human female average. So we were able to reject our previous hypothesis that Issa was characterised by “hyperlordosis” (at the extreme end of modern human variation, or excessive lordosis)

She demonstrates other clear adaptations to bipedalism, like widening of the inter-articular facets of the lumbar vertebrae, which form a “pyramidial configuration” and allows weight transmission of the upper body down through the lower back.

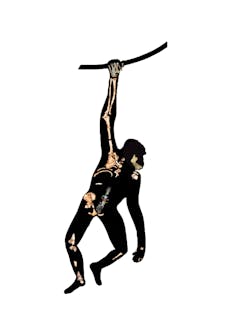

However, Issa also has features that suggest she was a tree climber. She had a powerful lower back for hoisting herself in trees and hanging below branches. That mosaic of features is typical of other body parts of A. sediba and confirms that the species walked bipedally on the ground but climbed trees like apes do.

Does this help us to locate the species on our human family tree?

To approach A. sediba’s evolutionary relationship to other hominins, character-based analyses of the whole body are needed, and we’re getting more and more of A. sediba every year. Given what this and other research has shown, I think it’s a candidate for a close relative of the genus Homo. Hopefully Issa’s skull was not destroyed by miners: recovering that and other body parts from both her and Karabo will go a long way in resolving the debate.

Is there a way for others to study the fossils?

3D models of the new fossils, all previously published fossils, and our reconstructions are available online. Anyone is welcome to download and study them to repeat our analyses, conduct analyses of their own, or 3D print them for teaching or other purposes.

The fossils themselves, curated at Wits University in South Africa, are also available for study by qualified researchers. The more open the access is, the better the science will be as individuals from diverse training and backgrounds will undoubtedly make novel observations and strides towards a better understanding of human evolution.

Scott A. Williams, Associate Professor of Biological Anthropology, New York University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.