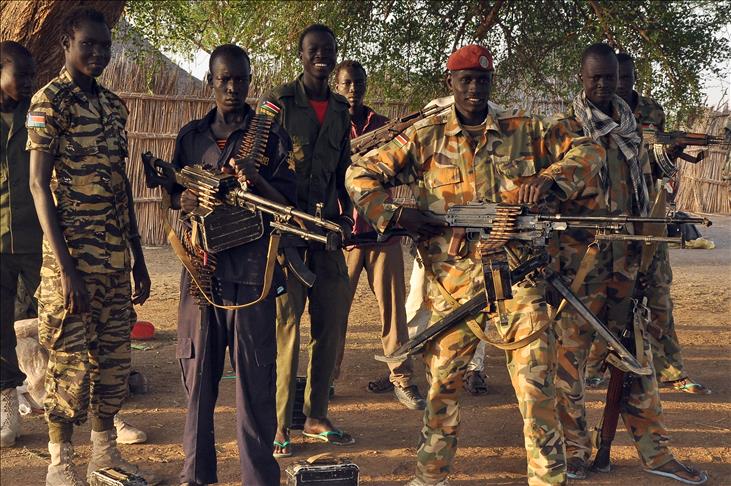

South Sudan is experiencing extreme political tensions that many fear could lead to war again, while misinformation and hate speech on the internet are escalating the country’s anxiety and divide.

Around 400,000 people lost their lives in the bloody civil war that raged from 2013 to 2018 due to ethnic conflicts, especially between the two main communities, the Dinka and the Nuer.

Nelson Kwaje, chair of Digital Rights Frontlines, a Juba-based NGO that tracks hate speech and false information online, said that after years of relative calm, there are concerning indications of the resurgence of ethnic polarisation.

This comes as President Salva Kiir’s 2018 peace deal with his longtime opponent, First Vice President Riek Machar, who is Dinka and Nuer, respectively, is in jeopardy following Machar’s detention on Wednesday.

He added that just 40 to 50 per cent of people have a mobile phone, and a realistic estimate of social media use is about 10 per cent.

But those who have access are frequently “the loudest voices,” and their messages contaminate the air as they circulate communities through more conventional channels.

Speaking from Juba to AFP, Kwaje claimed that city life remained “relatively calm.”

However, “social media disinformation and hate speech, which is very intense” is feeding people’s anxieties.

“There are rumours of assassinations, talk of retaliatory violence… warnings about ethnic violence,” he noted.

– Videos have ‘radicalised people’ –

The first was the vicious murder of an army commander who had been taken prisoner by the White Army, a mostly Nuer militia, and the second was a video that seemed to depict a young Dinka male being brutally abused by individuals with Nuer accents.

Kwaje claimed that although ethnic division had decreased significantly in recent years, such films have “radicalised people” once more.

“The polarisation is very clear,” he stated. “If more incidents go in this direction, it will go to the next level of people taking up arms.”

“In South Sudan, access to reliable information and free media is restricted.” It makes a hoover,” Kwaje stated.

“Not everyone who fills the void is evil; many merely wish to exchange information to safeguard their society.

“But then you have actors who want to fan engagement and a small section who are politically motivated.”

Kwaje claimed that although these political messages were well-crafted and consistent, it was difficult to determine who was behind them.

“When we see that level, we know there’s someone on a payroll. Now we have better shock absorbers. There was a very clear tribal divide when the civil war broke out in 2013,” he stated.

According to Kwaje, the peace deal that put an end to the conflict in 2018, “for all its faults,” involved the international community, disbanded and partially merged the troops of Kiir and Machar, and imposed an arms embargo that somewhat restricted its supply.

“Young people understand the risks of tribal division as well. A lot of messages are about peace. Sharing content that depicts a member of your tribe being abused, however, is what drives individuals to the brink. The content instantly radicalises you, regardless of its veracity.”