An increasing number of patients are seeking care at Nyiragongo General Referral Hospital in Goma, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, amid a rapidly spreading mpox epidemic.

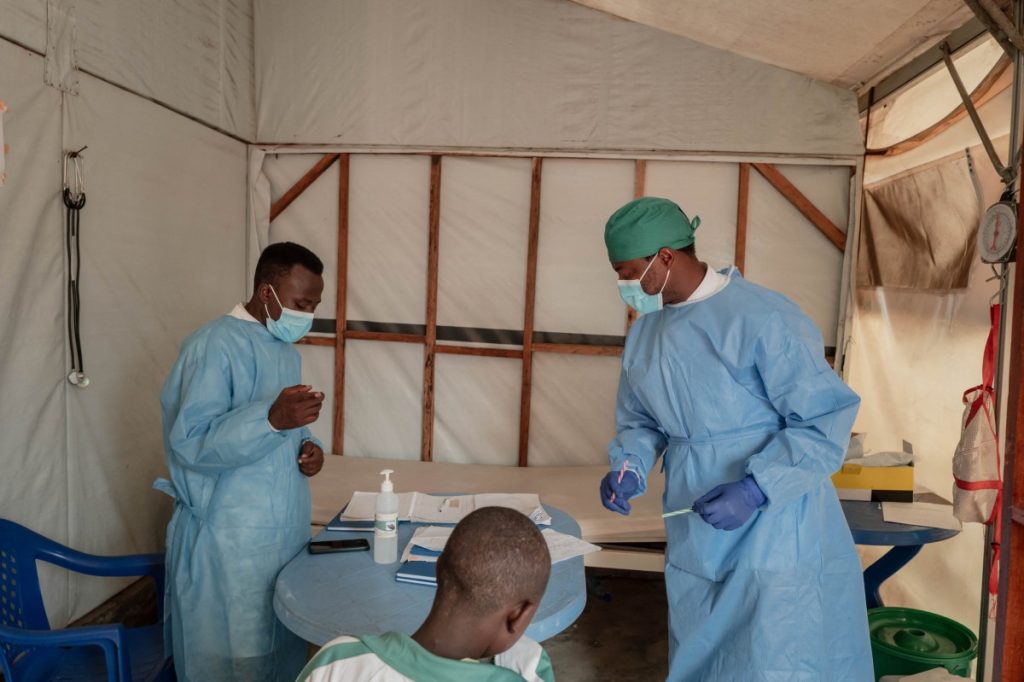

Each day, five to twenty individuals consult with overwhelmed medical teams at the hospital’s outdoor isolation centre, concerned they may be infected with the virus.

Mpox can be transmitted from animals to humans and through close human contact, including sexual activity.

Dr. Tresor Basubi examined a calm girl with skin lesions from the disease, which has killed 548 people in the DRC this year alone.

Cases have now appeared in every province of the DRC, which has a population of 100 million.

“This is just the beginning; the child is active and doesn’t show severe symptoms,” Dr. Basubi noted during his examination.

Most infections are benign and treatable with medications like paracetamol for fever and zinc oxide cream for lesions.

“Patients experience itching, but scars fade over time,” he added.

While mpox has been reported before, a new, more deadly strain—clade 1b—has emerged, causing mortality in approximately 3.6% of cases, particularly among infants and children, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

The DRC, which has recorded around 16,000 cases this year, is at the centre of an epidemic that prompted the WHO to issue its highest international alert level.

South Kivu province alone reports about 350 new cases weekly, according to epidemiologist Justin Bengehya.

Goma, surrounded by armed conflict and housing hundreds of thousands of displaced individuals in makeshift camps, is particularly vulnerable to widespread transmission due to overcrowding.

There are approximately 7.3 million displaced persons in the DRC, as reported by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

At the treatment facility, parents held their infectious children, risking skin-to-skin transmission even as staff sought to educate them on prevention.

“My son was hospitalized for mpox, and after caring for him, my daughter began showing symptoms days later,” said Deogracias Mahombi Sekabanza, a health worker whose children both fell ill.

Sekabanza explained that his son got the disease after playing with friends.

Furaha Makambo, living in a nearby tent with her three infected children, expressed concern.

“My children share a bed, and I couldn’t separate them,” she said, having fled her home in Masisi after her husband died amidst violence from armed groups.

“I’m scared; this disease must be eradicated to protect the displaced,” she told AFP.

Although experience from previous outbreaks aids staff in responding swiftly, children often struggle with maintaining social distance.

“This disease spreads rapidly. Touching the sweat, urine, or clothing of an infected person puts you at risk,” Dr. Basubi explained.

“Washing hands with soap or ashes can help, but it’s not foolproof,” he added.

In a tent with three other children from different families, displaced vendor Nyota Mukobelwa laughed in front of the cameras.

“We need vaccines available; otherwise, this epidemic will continue, leading to more deaths and contamination among our children,” she stressed.

The WHO has called for increased production of mpox vaccines and urged countries to donate stockpiles to areas affected by outbreaks.