It’s easy to throw stones from the sidelines until you remember glass houses don’t forgive. The ongoing feud between Afe Babalola and Dele Farotimi exemplifies this precarious balance between free speech and responsible discourse. For a while, I chose to watch in silence, absorbing the charged albeit insightful commentaries, until I stumbled upon Abimbola Adelakun’s incisive piece titled “Afe Babalola: Of a Man and His Weakness.”

In Nigeria, there’s a law stating that anyone who calls a woman a prostitute without evidence faces up to three years in prison for criminal defamation. Just last week, an Oredo Chief Magistrate Court in Benin, Edo State jailed the proprietor of Calvary Crown Academy, Paul Okugbowa, and three teachers for six months with an option of N100,000 fine for calling the mother of a pupil a “prostitute.”

While that law targets specific claims, its principles could well apply to broader scenarios—such as accusing someone of bribery without concrete proof.

From the little I know,defamation, protection of personal data, and privacy laws are based on the constitutional right to privacy provided for under section 37 of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended). It offers the “Right to private and family life: The privacy of citizens, their homes, correspondence, telephone conversations, and telegraphic communications is hereby guaranteed and protected.”

Also, at common law, anyone involved in the publication of a defamatory statement, no matter how slight, including a newspaper vendor who may be unaware but merely sells newspapers allegedly containing offensive materials, may be liable for defamation.

However, with the advent of social media and other digital platforms, such as TikTok, X, Websites, Facebook, Instagram, search engines, and other means of online expression poses new challenges.

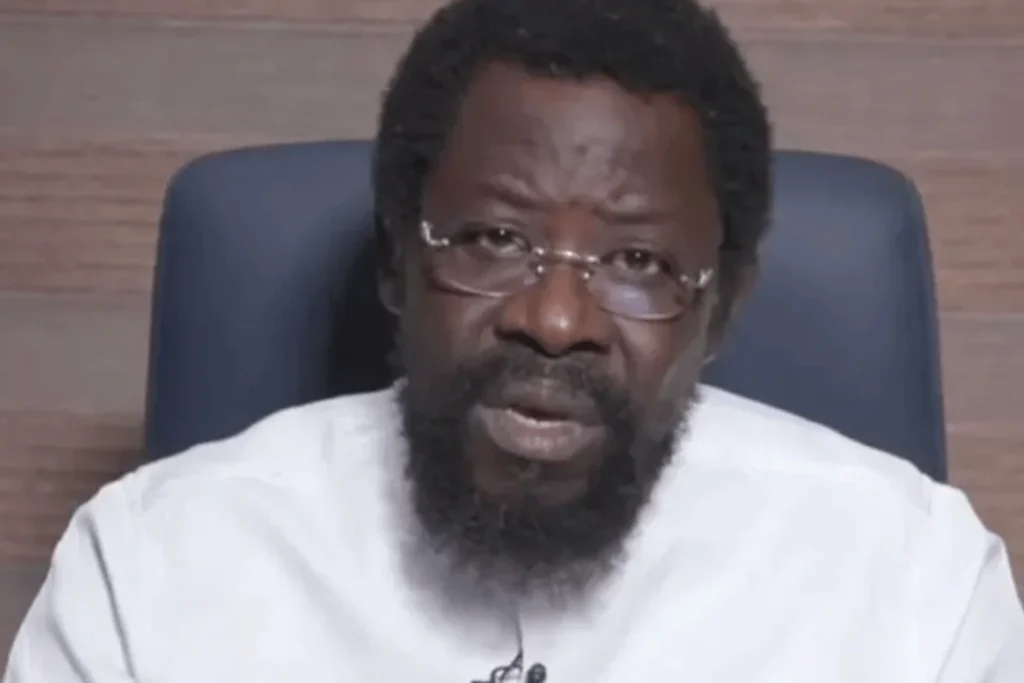

This is where my concerns with Dele Farotimi emerge. If he opted not to appeal as one of the lawyers involved in the Eletu case, learned Silk Oluwole Aladedoye SAN stated on Arise TV on Wednesday, he should have armed himself with undeniable evidence—proof of barters, favours, bank statements, recordings, or video proof—to back his allegations that Afe Babalola accepted bribes. Without such evidence, these accusations are dangerously close to mere gossip.

Aladedoye listed out the facts of the matter leading up to the Supreme Court’s decision.

Documenting bribery claims in a book elevates the stakes dramatically. As a lawyer, Farotimi should have understood the legal and reputational fallout of making such assertions without irrefutable proof.

This form of activism—one rooted in reckless accusations—risks eroding not just personal credibility but public trust in advocacy itself.

Afe Babalola, a globally respected lawyer, has cultivated an impeccable reputation over decades. Proven corruption allegations would undoubtedly tarnish his standing, both locally and internationally. However, without evidence, such claims only serve to unjustly soil his character and fuel a toxic cycle of unverified slander.

Sadly, this is emblematic of a larger issue: some Nigerian activists thrive on whipping up emotions, often relying on the gullibility of their followers rather than engaging in fact-driven advocacy.

This approach undermines the very causes they claim to champion, doing more harm than good in the long run.

As an experienced lawyer, Farotimi should know better. Making allegations without evidence not only breaches legal and ethical norms but also undermines the integrity of public discourse.

The legal profession demands adherence to principles that prioritise facts over baseless claims, and this case reminds us why.

That said, this ongoing saga presents a teachable moment. Beyond the drama, it offers an opportunity to educate the public and reinforce the importance of accountability, even within the bounds of free speech. Ultimately, whether the case ends in triumph or defeat, it serves as a reminder of the legal, ethical, and professional standards that should govern public engagement.