I grieve to start this way. No sooner had I struggled to find some means to say my goodbyes to Mabi Thobejane and Steve Kekana, than South African music lost singer and composer Tsepo Tshola.

These three masters of the nation’s musical soul were famous, but not celebrities. Because they never acted like that. Complex personalities and talents, they all possessed that son-of-the-soil joviality that made them ever accessible and “simple” in the reverent way South Africans use that adjective.

I remember, in 1978, during one of my many research tours in Lesotho, a mountainous kingdom encircled by South Africa, I was hanging with the brilliant guitarist and composer Frank Leepa, drummers Moss Nkofo and the one and only Black Jesus (passing around the herb), and Tsepo, in a ramshackle old storefront across from Maseru Market.

They were Uhuru Band back then, and flushed with the success of their first hit song, simply entitled Africa. The song merely praises and celebrates the mother continent, yet so repressive was South Africa’s apartheid regime that the band was banned from performing there. Their manager, Peter Schneider, pondered what to do. Shuffle the personnel a bit and change their name, I shrugged. And so eventually did they re-emerge as Sankomota – Lesotho’s most famous Afro-fusion pop ensemble.

Tsepo would go on to bridge Lesotho and South Africa in a time of political tumult. What drove his life and his music would be his fierce sense of belonging to both nations as one.

The life

He was born in 1953 in the Berea district of western Lesotho, in the “one-street” but scenic town of Teyateyaneng or TY. Tsepo, however, had other inspirations for his musical vocation than the late-night dances at TY’s famous Blue Mountain Inn.

His father Mokoteli was a pastor with the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and both the Reverend Tshola and his wife MaLimpho were stalwarts of the double vocal quartet the Vertical 8. Tsepo always emphasised this church as his musical alma mater, with its liturgical roots in African-American hymnody (the singing or composition of hymns).

By 1970 he had already joined Leepa, and they would form Uhuru in 1975. In the late 1970s, now as Sankomota, they were the house band at Maseru’s Victoria Hotel, entertaining luminaries such as Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela, exiled from South Africa by their politics.

1983 was their breakout year, with South African producer Lloyd Ross of Shifty Records recording their first album, Sankomota, and the release of Leepa’s hit composition It’s Raining. With Masekela, Tsepo toured southern Africa and ventured to London, where the rest of Sankomota joined him in 1985.

Returning from London as Nelson Mandela’s release from prison and the end of white minority rule approached, Tsepo then joined Masekela for his epochal homecoming Sekunjalo tour of South Africa in 1991. Masekela was stunned by the massive adulation with which he was greeted by audiences (including me) that he feared had forgotten him.

Read more: The Village Pope has passed: remembering Tsepo Tshola, Lesotho’s musical giant

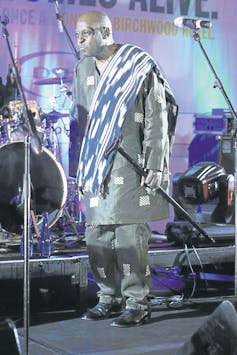

Tsepo seized the opportunity to begin what would be his legendary solo career, one that would last until his heartrending departure on 15 July 2021. Collaborating and leading the vocals for countless top artists and ensembles, his gravelly “Louis Armstrong” baritone would drive gospel, traditional and pop songs in Sesotho and under the name The Village Pope.

The spirit

The intertwining of inner spirit, life and art in Tsepo Tshola’s odyssey cannot be overemphasised. Let me illustrate this through the songs.

Tsepo was astonishingly prolific, and he continued composing, recording and performing almost until his death. Of this monumental catalogue, however, a few are sure to be played as long as the turbulent, ebullient decades leading up to and following the turn of the 21st century are remembered. These include one of the earlier works, Papa, from Sankomota’s album Writing on the Wall (1989). https://www.youtube.com/embed/4s4jbA3TUgQ?wmode=transparent&start=0

Religious in tone, as ultimately with all of Tsepo’s music, the song includes a solo verse as much intoned in prayer as sung in his raspy voice:

You’re waiting for your name to be called (What do you say?) Your body is shaking with disbelief (Tell us more)…

In 1994, a newly democratic South Africa witnessed the release of Tsepo’s signature album, The Village Pope, the one that forever gave him his name as iconic pastor of South African pop.

Most of the tributes that have poured forth in print and on social media have included this jaunty, iconoclastic alias. Yet it is not at all an attempt at self-congratulation or promotion, nor a reference to his sometimes harshly paternalistic admonition of his musicians in rehearsal and recording. It is rather an honorific proclaiming his unwavering commitment to kith and kin; his home in Lesotho, his close friends and family, his bi-national identity.

Upliftment

Avoiding the trappings of fame and shallow, transactional relationships, Tsepo was a devoted husband who never got over the passing of his wife in 1984. He never remarried, but remained, as many a Mosotho patriarch will sigh, “everyone’s father”. He was back in Teyateyaneng for a family funeral when he fell ill with COVID-19 and passed away.

Other songs of special significance include Holokile (All Right) from 1994, based in hymnody and virtually a hymn in itself. Indeed, Tsepo’s style has often been labelled “traditional gospel” but this is definitely the wrong music store bin. https://www.youtube.com/embed/aoN1rudM-2s?wmode=transparent&start=0

Tsepo’s style comes from a blending of the Afro-pop fusion of “black consciousness” groups such as Sakhile, Stimela, and of course Frank Leepa’s Sankomota in the 1980s, and his own hymnodic upbringing. That is why his songs are more inspirational than celebratory, and more “step and sway” than danceable. They are ballads to uplift an African nation.

Stop the War, from 1995, is not a religious tune at all, but an upbeat, pop injunction to South Africans not to fight one another over the spoils of the victory over apartheid. During the looting and insurrection that was taking place on the very day of his death, Stop the War was the song heard on radio stations nationwide.

Finally, there is his rollicking, township-jiviest song (no gospel here), Akubutle (Don’t Ask), from 2003, the one that never fails to bring listeners to their feet at a restaurant, club or party.

BT, as Bra Tsepo was popularly known, we can’t blame you for leaving us, but how are we going to get through all this without you? Akubutle.

David Coplan, Professor Emeritus, Social Anthropology, University of the Witwatersrand

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.