Ine Van Caekenberghe, Ghent University

Stretching back to pre-colonial Rwanda, a unique athletic performance akin to modern-day high jumping formed part of regular ceremonies in the royal court. Known as Gusimbuka Urukiramende, this type of jumping appears to have been practised in three main contexts. First by selected groups of youth, known as intore, performing before the king or chiefs; at royal festivals and weddings and as a form of popular recreation.

Spectators would have cheered the exploits of young, athletic and tall performers jumping in sequence over a bar (usually a wooden stick) placed in between two makeshift posts. In front of the bar would be a stone or some kind of termite-hill like structure marking the spot where athletes would spring from their feet.

In the first half of the 20th century foreign spectators of the traditional performances were in awe of the jumping heights reached by these athletes. In pictures taken at the time, we see athletes jumping over people standing underneath the bar. In the most famous of these pictures, taken in 1907, two eye-witnesses stand beneath as a jumper clears the bar at a reputed 2.50 metres.

Some witness accounts reported “performances fit for the Olympics” and:

A spectacle that has never been seen at the Olympic games.

If accurate, these performances would still beat today’s high jumping world record of 2.45m. Since Gusimbuka Urukiramende athletes used a suboptimal technique for high jumping compared to their international peers, this would be quite remarkable. Unlike today’s athletes, these high jumpers crossed the bar in a rather upright position. This means that they had to elevate their bodies higher to clear the same bar height.

However, no official measurements of bar height in Gusimbuka Urukiramende ceremonies could be retrieved. And nor did these athletes compete internationally, making it impossible to verify the astonishing performance claims. By the early 1960s Gusimbuka had disappeared as the monarchy in which it thrived was abolished. Nevertheless, there is recent footage of Kenyan jumpers using the same technique.

My colleagues and I therefore set out to study the achieved jump heights by these athletes and to compare them to performances of contemporary high-jumping athletes in the rest of the world. This would help to verify the claims about world records and performances worthy of the Olympics.

Our analyses demonstrate that these athletes did not jump as high as the world record. But their performances were still worthy of the Olympics finals – and potentially even a medal.

Examining the archived record

We searched various Belgian archives for photographs and cine films of Gusimbuka Urukiramende. We settled for three photographs for further analysis.

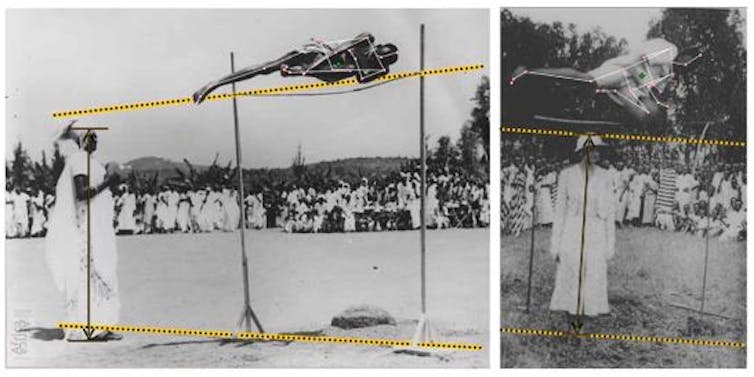

In two of the photos from 1939, Rwandan king Mutara III Rudahigwa stands next to one upright. In another, from 1934, Belgian Queen Astrid stands underneath the bar. For these photos, the jump height could be calculated and expressed in metres by comparing jump height to the known body heights of the queen and king.

Our research team also identified 19 jumps in cine films for analysis. For the cine films jump height could be expressed relative to athlete body height.

To extract the information, the original film was scanned and stored in a digital format. The vibrations of the film were then cancelled. Anatomical landmarks were digitised on the athlete and the athlete was represented using a biomechanical model to calculate the body centre of mass. This is a landmark that summarises the movement of the entire body. To arrive at the jump height, some final steps were taken:

- The images were rotated so gravity was pointing downwards

- The floor level was estimated in the images

- Perspective in the images was accounted for and, finally

- Jump height could be calculated

When standing upright, an athlete’s centre of mass is located in the abdomen. Our calculations showed that Gusimbuka Urukiramende athletes could reach heights with their body centre of mass of up to 2.38m, or about 135% body height. However, an athlete’s jump is determined at the lowest point of the body at the apex of the jump. This point is, in Gusimbuka Urukiramende, always lower than the body centre of mass because of the technique used.

In Gusimbuka Urukiramende, athletes raise their entire body over the bar instead of the gradual passing in the modern-day Fosbury Flop technique. This means that Gusimbuka Urukiramende athletes would have had to raise their body centre of mass about 15% body height higher than the bar to clear it, whereas athletes using the Fosbury would only need 1 to 2% body height.

The maximal bar height that Gusimbuka Urukiramende athletes could cross in our dataset was 2.16m or about 120% of their body height. The current world record stands at 2.45m.

Additionally, Gusimbuka Urukiramende athletes took off from a stone of 0.23m or about 12% of their body height. Not only does this elevated take-off need to be subtracted from their jump height, but also the additional beneficial effect of taking off from an elevated surface must be considered. The athlete does not only gain this 12%, but on top of that the athlete can jump about 0.05m (or 3% body height) higher compared to not using an elevated take-off surface.

This added effect was estimated at about 0.05m or 3% body height. Thus, when correcting for the stone height and its additional effect on performance, athletes could have cleared a bar height of 1.88m or 106% body height.

Olympic standard

Did Gusimbuka Urukiramende jumpers achieve world record heights? Our evidence does not support this claim.

A jump height of 1.88m, while of high standard, would not have beaten the contemporary world record. At the time the pictures were taken (1934-1939) the world record increased from 2.06 to 2.09m. A height of 1.88m would only have been a world record prior to 1876.

In defence of the Gusimbuka Urukiramende athletes, the pictures might not have been taken at the highest point in their flight. So, their jump heights could have been a little bit higher, but the difference probably still wouldn’t bridge the gap to the contemporary world record.

Yet, when comparing Gusimbuka Urukiramende jump heights (the best one reaching 106% body height) to performances in contemporary Olympic finals (in 1952 varying between 91% and 108% body height), the best Gusimbuka Urukiramende athletes would have been able to participate in Olympic finals and potentially also win a medal, even when using a suboptimal jumping technique.

Additionally, world record performances are unprecedented performances of exceptional athletes. It would have been a very lucky coincidence that such a phenomenal event was captured in our limited database of quantifiable Gusimbuka Urukiramende jumps. Therefore, we broadened our scope by investigating the claim that Gusimbuka Urukiramende jumpers could have delivered performances worthy of participation at the Olympic Games.

To this question, the answer is yes.

Ine Van Caekenberghe, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Department of Movement and Sports Sciences, Ghent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.