Peter Macharia, KEMRI Wellcome Trust Research Programme and Emelda Okiro, KEMRI Wellcome Trust Research Programme

Improvements in child survival globally have been remarkable. Deaths of children under five declined by 59% from 93 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 38 in 2019.

However, 5.2 million child deaths still occurred in 2019. Over half of these were in sub-Saharan Africa. And all five countries with child mortality rates above 100 deaths per 1,000 live births were found in Africa.

While Kenya had 43 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2019, our previous work showed big differences across the 47 counties since 1965. A range of factors were likely behind this. These included disparity in the coverage of interventions such as the uptake of childhood immunisations, supplements and breastfeeding practices. Other important factors include pregnant women attending antenatal care, having skilled birth attendants and delivering their babies in a healthcare facility.

We have conducted two studies that give granular insights into the situation in regions across Kenya. Between them the studies show which regions have insufficient coverage, which have high disease infection rates, and what factors have the greatest impact on child survival.

Our findings show that Kenya needs to focus its child care plans based on localities and populations with the greatest need. Prioritisation is key.

Our research provides a good starting point as an evaluation of what is currently in place – and what the threats to child survival are – at a local level. This is vital because national aggregates mask distinct differences across the country.

Big differences across regions

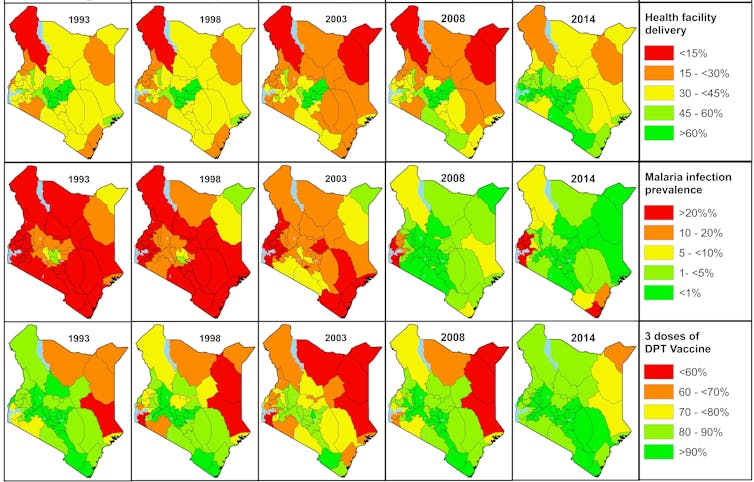

In our first study, we set out to explore disparities and inequities by estimating the coverage and prevalence of 43 determinants. This we did for each of Kenya’s 47 counties every year between 1993 and 2014.

In our second study, we evaluated the impact of the estimated determinants on child survival. We did this by using epidemiological impact evaluation approaches.

Our findings showed that in the early 1990s, the coverage of interventions was average. Coverage began to deteriorate through to early 2000. After 2006, there was an improvement in coverage of interventions and reduction in disease infection prevalence. Thirty-eight of the 43 mapped factors recorded an improvement over the two decades.

However, the improvement wasn’t uniform. It ranged between 1% and 898% (increase in coverage or decrease in disease prevalence) at the national level. For example, maternal literacy increased by 9.6% while the use of bed nets among children living in malaria endemic areas increased from 6.2% in 2003 to 61.9% in 2014, a percentage increase of 898%.

There were also marked differences across the counties. Considerable differences in the coverage between factors were observed at the county level, ranging from low (less than 35%) for improved sanitation to high (over 65%) for childhood immunisations by 2014.

Counties in Northern Kenya consistently showed lower coverage of interventions throughout the period up to 2014. They did, however, have lower malaria and HIV infection prevalence.

Areas around Central Kenya have historically had – and continue to have – higher coverage across all intervention domains.

Most counties in Western and South-East Kenya along the Indian Ocean recorded moderate intervention coverage across all factors. But they bear the greatest burden of HIV and malaria infection prevalence.

We observed correlation between performance and levels of investment in affordable and accessible healthcare services. Some of the interventions have included policies on user fee, expanded immunisation programmes for common childhood illness, schools, community and health facility-based initiatives. Control interventions for diseases such as HIV and malaria, integrated management of childhood illness and the impetus to improve child survival also made a difference.

Kenya has also made significant strides in promoting child health through legal frameworks. But floods, droughts, epidemics and post-election violence have made child survival more difficult.

Determinants that made a big difference

Our second study identified ten major determinants associated with changes in child survival in Kenya. They included: deliveries in a health facility, receiving all basic childhood vaccines, households’ access to better sanitation, seeking treatment after fever, HIV and malaria infection prevalence, infants’ breastfeeding within the first hour of birth, the prevalence of stunting in children, the number of children in a household and maternal autonomy. The autonomy factor was measured by assessing a woman’s personal power in the household and her ability to influence and change her environment.

Under-five mortality increased in the 1990s, which resulted in many children not living to see their fifth birthday. This trend was linked to rising HIV infection prevalence and reduced maternal autonomy.

After 2006 the high number of child deaths started to come down. This was associated with a decline in the prevalence of HIV and malaria, increase in access to better sanitation, fever treatment-seeking rates and maternal autonomy.

Reduced stunting and increased coverage of early breastfeeding and institutional deliveries (overall increased from 41.6% in 1993 to 62.2% in 2014 and averted 31,000 deaths) were associated with a smaller number of deaths averted compared to the other factors.

Again, there were wide variances across regions in Kenya.

The highest number of deaths averted was recorded in western and coastal Kenya, while northern Kenya recorded a slightly lower number. Central Kenya had the lowest number of deaths averted.

A unique set of factors contributed to these wide differences.

Read more: What mapping Kenya’s child deaths for 50 years revealed — and why it matters

What needs to be done

Our research provides an additional tool for determining what to prioritise, where to target and when to intervene. The Commission on Revenue Allocation, which allocates funds to county government, can use it to inform the allocation of funds.

Divisions within the ministry of health such as the national malaria control programme and international development partners can also use the estimates to evaluate the impact of interventions and funding or justify support for outreach programmes.

The findings also form a baseline for monitoring sustainable development goals, county-specific targets and inputs in epidemiological studies.

The framework can be applied to update estimates and evaluate progress at a more granular level such as the sub-county level as new data sources become available, including data from the 2019 census or the revamped routine health information system.

Decisions based on the findings and recommendations will improve child survival and enhance health equity across Kenya’s 47 county governments, getting closer to ensuring no child is left behind.

Peter Macharia, Newton Int’l fellow at Lancaster University and Visting researcher, KEMRI Wellcome Trust Research Programme and Emelda Okiro, Head of Population Health Unit, KEMRI Wellcome Trust Research Programme

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.